The Linothorax/Spolas (Tube and Yoke Body Armor)

By Andrew Yamato

Despite its ubiquity in ancient art, the “tube & yoke” style of Greek body armor remains mysterious and highly controversial.

My first reconstructions were tapered composite corselets of segmented construction.

My second generation tapered corselet uses the same linen over leather composite construction, but was made from a single piece of leather.

The nature of Greek “tube and yoke” (T-Y) armor is perhaps the most heated and enduring debate regarding the hoplite’s material culture. There is not even agreement on what to call it: “Type IV” in Eero Jarva’s taxonomy; “linothorax” if made from linen; “spolas” if made from leather, or simply the generic “corselet.” With the exception of a single example made in iron (presumed to belong to Philip of Macedon, and overwhelmingly regarded as atypical), no complete example of this pattern of armor has been found, despite its apparent ubiquity on ancient battlefields for over half a milennium. This strongly suggests construction from organic materials, with the two main contenders being leather and linen. Both have their partisans.

Without attempting to summarize the entire debate (a task which Dr. Paul Bardunias has accomplished very well here), suffice it to say that the form of T-Y armor (i.e. a “tube” wrapped around the torso, split at the bottom into a skirt of strips called pteryges (feathers), with a U-shaped “yoke” attached to the back and reaching over the shoulders to attach in front) is so simple and effective that similar armors have been devised in cultures far beyond the Greek world. Given the many centuries that the Greek version was in use, and the many different (and differently resourced) peoples which used it, I suspect that this armor was to some extent made with whatever protective material was most readily available – leather in cattle country, linen where flax was grown – and in whatever quality or thickness the wearer could afford. The artistic record also suggests that many armors were in fact made of composite materials – linen and leather, perhaps, often supplemented with metal or hide scales and plates.

The use of linen in Greek armor is not controversial – there are numerous manuscript references to linen armor which almost certainly refer to T-Y cuirasses. It is, rather, the manner in which it was used that inspires debate. An earlier consensus of glued laminated linen armor (based on speculations and reconstructions made by the late Peter Connolly) has largely been displaced by a new orthodoxy which insists that linen was quilted (as in medieval gambesons) or twined (a laborious process which to my knowledge has yet to produce a single replica cuirass) but NEVER glued. This second camp cites an admitted near lack of hard evidence for glued linen, but given a near complete lack of evidence for this armor generally, such categorical proclamations are problematic. There are proven protective benefits to the bonding of linen layers with some sort of adhesive into a stiff, solid mass; not only an approximately 15% greater resistance to arrow penetration (according to Dr. Gregory Aldrete’s well-known if oft-mocked study), but also the universal physical fact that hard material is better able to absorb and distribute blunt impacts than a “soft” material of otherwise identical construction. The stiffening/bonding agent need not be glue, either. The protective stiffening of laminated linen armor with salt and vinegar (or wine) was a technique well-known in later antiquity, and may well date back much earlier.

The theory of twined linen armor (similar to a thick, densely knotted knit) is currently quite fashionable, in large part because it is described in detail by ancient sources. The problem, aside from the aforementioned difficulty of production, is that both ancient mentions of twined armor are in reference to royal possessions – in one instance the temple offering of a Pharaoh, and in the other, the personal “2-ply” armor of Alexander the Great himself, looted from the Persians at Issus – which we can fairly assume were lavishly atypical. In any case, it seems that twined armor would have had to have been exceptionally protective to justify its laborious production, and as yet, we have no experimental evidence of this. We know that woven linen, on the other hand, was relatively common, and armor production may in fact have been an excellent use for worn-out or discarded clothing.

At the moment, the most popular theory of T-Y armor construction is leather – probably tanned cow leather, perhaps rawhide. This is mainly based on ancient references to a leather armor called a “spolas” which “hangs from the shoulders.” Putting aside the technical point that a well-fitted T-Y armor does not hang from the shoulders (but is rather supported on the hips), and my own doubts about embracing the term “spolas” on the strength of this single reference, it seems very likely that many T-Y cuirasses were indeed made from leather. Unscientific backyard testing, however, makes me doubt the relative ounce for ounce protectiveness of leather compared to laminated linen, and I don’t think it’s been conclusively established that leather was cheaper or more readily available than linen. (In any case, given the “no expense spared” aesthetic of privately purchased armor through the ages, I’m not sure cost was generally a decisive factor.)

The relative protectiveness of T-Y armor is, of course, the subject of its own debate more generally. Armor need not be impervious to be effective, and lightness is always a competing virtue. It’s very difficult to create a wearable organic armor that can’t be penetrated by a determined spear thrust, for example, but easy to make something that can stop an ancient arrow cold. We also see numerous artistic representations of T-Y armor being rolled up and handled as if it were a very slight thing indeed, perhaps protective only against glancing blows or spent missiles. Personally, given the common threat posed by arrows, I think effective protection against them would be a minimum standard for any armor worth wearing.

A sharp spear delivered with a determined thrust easily penetrates 16 layers of glued linen…

Five layers of vegetable tanned leather plus four layers of linen fares little better.

Making a Composite (Linen & Leather) Corselet

For my first attempts at making armor (see below for my model 2.0) , I settled on a somewhat agnostic synthesis in which core plates of heavy, dense, oak-bark tanned leather are wrapped in four layers of heavy linen (laid crosswise to each other to maximize weave density and penetration resistance) that has been saturated in a traditional artist’s gesso of rabbit glue and white kaolin clay. In addition to producing a fine canvas surface for painting, the kaolin gesso binds the linen sheets to themselves and their leather backing, producing smooth, flexible, white plates which very closely resemble what we often see in art. The kaolin gesso, once worked into the fibers of the linen, does not flake off even with flexing, and can be renewed with additional applications.

The leather core plates are wrapped in linen.

Each of the four layers of linen are laid at a 45º angle to the previous layer.

The integral outer pteryges are cut.

Rabbit glue is used to adhere the first layer of linen to the leather.

A gesso of kaolin clay and diluted rabbit glue is applied to each layer of linen.

When finished, the kaolin-saturated linen-covered leather armor is stiff yet flexible, with no loose clay.

My use of kaolin clay is entirely attributable to Dr. Paul Bardunias, who has noted that kaolin – a common material found locally in Attica that was used both as a ceramic slip on Attic pottery and as a bleaching agent for clothing – is used in modern ballistic body armor because of its non-Newtonian “shear thickening” properties. Very approximately, this is a molecular structure similar to that of a cornstarch oobleck which assumes greater viscosity as “shear rate” (e.g. resistance to penetration) increases; in other words, it’s a fluid/flexible material that momentarily acts like a solid at the moment and location of impact. Personally, I have tried and failed to produce such an effect with kaolin, and I doubt that the Greeks would have been even vaguely aware of this effect themselves; my decision to use kaolin gesso derives from the protective seal and satisfying matte white appearance it gives to our armor, which also has the virtue of being renewable with subsequent applications of kaolin, in much the same manner that generations of British soldiers have whitened their buff leather gear with pipe clay.

The interior pteryges are staggered and stitched behind and slightly lower than the outer layer of pteryges.

After the plates are tightly sewn together, the seams are covered and the edges are bound with soft leather.

There appears to have been some variety in the shape/cut of T-Y armor, with some “tubes” being just that – straight and seamless, cut at the bottom into pteryges. Being confident that vanity is one soldierly constant through the ages, I made a more complicated pattern of slightly trapezoidal sections to impart a more masculine V-shape silhouette to our armor. The seams were then stitched and covered with the same soft leather I used to bind the plate edges, giving a close resemblance to sectioned and shaped armor seen in vase art. Each plate was cut into 2” wide pteryges at the bottom, with a second later of pteryges stitched behind and slightly lower than the first.

As previously mentioned, a properly fitting cuirass will sit on the wearer’s hips, close to the body, with little or no weight on his shoulders. The pteruges should extend no further than the crotch. The yoke should extend approximately the same length in front and in back, with the raised neck-piece extending above the shoulder-line and fitted closely to the neck. The arms should have unrestricted movement.

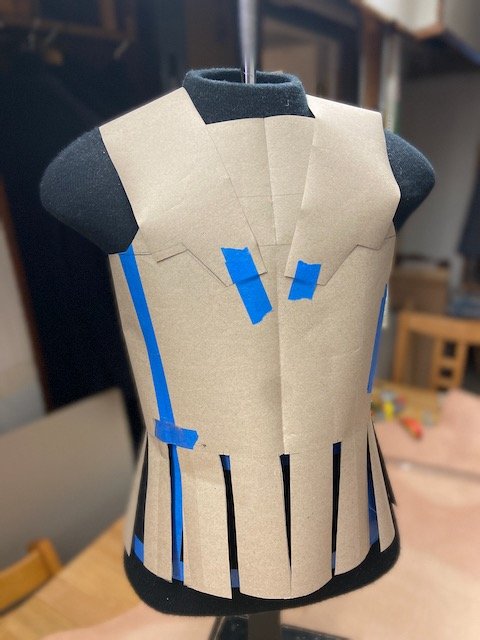

For anyone looking to make their own armor, I cannot overestimate the importance of starting with a cardboard pattern. There is no substitute for determining correct fit and proportions. Bear in mind that thick leather also bends/folds differently than cardboard, so be generous with your dimensions or you’ll be wearing a corset instead of a corselet. Or so I’ve heard.)

I used brass drawer pulls for the rings and rosettes (bronze replicas of originals are available, but expensive) which attach with prong fasteners that bend back on the interior of the armor. The exposed tabs are then covered with glued leather pieces and a soft full pigskin lining makes everything neat and comfortable.

In the numerous hoplite arming scenes we see in vase art, we invariably see unfastened epomides (the front extensions of the yoke) standing upright as if spring-loaded. This feature has been much discussed as it seems to offer a clue into the material from which the armor is made, and probably has done much to account for the popularity of stiffly glued linen armor.

As many reenactors have found however, this springiness doesn’t last long once the armor has been worn a bit, regardless of the material. My own theory is after a battle, hoplites would return home, wash the blood off their armor, perhaps reapply some whitening clay gesso, and hang it up flat against the wall to dry, where with the rest of their panoply it could be proudly and efficiently displayed in a modest Greek home. The next time the armor was taken down, the epomides would remain rigidly upright until pulled down and laced.

A post-event scrubdown.

Applying a fresh coat of kaolin gesso.

Vase art shows an almost infinite variety of decorations of T-Y armor, ranging from functional armor (e.g. scales) to purely ornamental elements like painted gorgons or stars. To the extent that many decorative elements were bronze (e.g. repousse bronze plates) they would have served both protective and ornamental purposes. Metal and/or hide scales appear everywhere and anywhere on artistic representations of T-Y armor, and it is a matter of ongoing debate whether their presence indicated a desire for protection in addition to that afforded by the underlying main armor, or whether the scales were mounted on flexible backing to protect vulnerable points of flexibility or articulation.

Making a One-Piece Composite Corselet

Although most vase art shows corselet “tubes” of segmented construction similar to that described above, there are depictions (notably on the frieze of the Siphnian Treasury in Delphi) that appear seamless — often while retaining a tapered silhouette. Rarer still are depictions of T-Y corselets where the tube and yoke, rather then being two attached pieces, appear to made in one piece — presumably cut from a single hide. For my second generation of T-Y armor (commissioned by my friend and fellow Greek Phalanx member David Anthony), I wanted to combine these attributes to create what I believe to be the first reproduction of a tapered single-piece corselet.

The frieze of the Siphnian Treasury (c. 525 BCE) is one of our most detailed and realistic depictions of hoplite panoplies of the late Archaic era.

A corselet cut from a single hide. Note the single layer of pteryges.

Eero Jarva's pattern for single hide thorax construction.